In May, a strain of ransomware known as WannaCry infected more than 230,000 computers in 150 countries, demanding about $300 in the cryptocurrency bitcoin to restore access. Primarily striking Europe and Asia, the attack crippled operations for a wide swath of enterprises, from the U.K.’s National Health Service to German state railways to thousands of private businesses. Although the buzz had died down, some businesses were still struggling to recover over a month later. On June 21, for example, despite efforts to secure its systems at the height of the attacks, Honda had to halt production at one of its vehicle plants in Japan after finding the ransomware in its network.

While most ransomware is spread through phishing, the WannaCry attack used an exploit called EternalBlue that takes advantage of a vulnerability in computers running outdated, unpatched versions of Microsoft Windows. The exploit is one of the National Security Agency-developed hacking tools leaked last year by hacker group the Shadow Brokers.

Experts warned that WannaCry may be a test balloon of sorts—cybercriminals trying to see just how much worldwide havoc they could wreak. Given the relative technical ease of launching a ransomware attack, the hackers netted a decent haul: At the beginning of July, bitcoin wallets associated with WannaCry had accrued a little over $120,000.

It has become a cliché with so many cyberrisks that the question is when, not if, a business will face the threat, but this aphorism is perhaps most accurate when it comes to ransomware. Last year, the FBI recorded more than 4,000 attacks a day, a 300% increase over 2015, and cybersecurity firm Kaspersky Lab reported that ransomware attacks on businesses went from one every two minutes in January 2016 to one every 40 seconds in October. Whether deployed for strategic disruption or for quick cash-grabs, with ransomware available for purchase on the dark web and the considerable efficacy and ease of launching attacks, the threat only grows.

“With the onset of ransomware as a very volatile yet easily findable tool to deploy without much sophistication from a hacking standpoint, it has really become about knocking on as many doors as possible to see if someone answers,” said Bob Wice, U.S. focus group leader for cyber insurance at Beazley.

Ultimately, a ransom payment is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to cost. Cybersecurity Ventures predicts that ransomware damages will exceed $5 billion in 2017, more than 15 times greater than the total from 2015. These costs include damage and loss of data, downtime, lost productivity, post-attack business disruption, forensic investigation, restoration of data and systems, reputation damage, and employee training in direct response to an attack.

Indeed, watching recent attacks unfold, the true toll of WannaCry for organizations may be forcing recognition of these real risks and escalating the conversation—and perhaps panic—over a critical threat that demands preparation.

“WannaCry and other ransomware has demonstrated that the biggest impact to an organization is not the ransom itself, but the associated business interruption, and that has really changed the dialogue because more companies are realizing that the potential financial statement impact is something they really need to be focusing on,” said Stephanie Snyder, national sales leader for cyber insurance at Aon Risk Solutions.

If At First You Don’t Prepare…

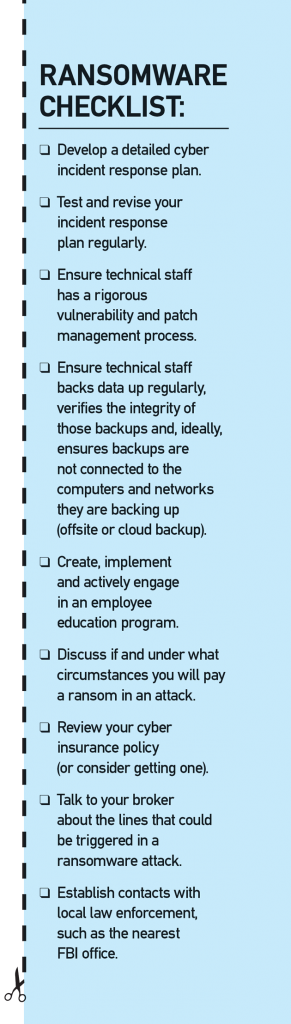

Because the stakes are so high, it is critical for organizations to have a clear strategy for responding to a ransomware attack. The first step happens long before you ever see a lock screen and a bitcoin demand—planning for it.

long before you ever see a lock screen and a bitcoin demand—planning for it.

In a June survey by ISACA, an international association of IT governance professionals, 62% of respondents reported experiencing ransomware in 2016, but only 53% have a formal process in place to address it, and 16% have no incident response plan at all. Deloitte also recently found that, despite notable confidence from business leaders, preparation for a cyber crisis lags. While 76% of executives felt highly confident in their ability to respond to a cyber incident, 82% said their organization has not documented and tested cyber response plans involving business stakeholders within the past year, and 21% lack clarity on cyber mandates, roles and responsibilities.

“Having an incident response plan is synonymous with cyber resilience,” said Rocco Grillo, executive managing director and cyber resilience global leader at cyberrisk management and incident response firm Stroz Friedberg. “Strategically, when we’re talking about the incident response plan, you should also be thinking in terms of how updated it is, whether it has been tested, and if it has been tested for situations like this.”

An incident response plan is a repeatable process that serves as a framework to guide companies through a crisis. Forging relationships proactively and gathering these resources in the incident response plan is key. Grillo called the core team needed in the room for crisis management “the six in the box: an outside forensics investigator, outside counsel, crisis communications, your cyber insurer or broker, notification and communications companies, and some type of relationship with law enforcement.”

In guiding companies through both preparation and crisis response, Grillo finds perhaps the biggest determinant in crafting a strong plan is communication between risk managers and chief information security officers. “One of the biggest things companies come up short on is not including the appropriate stakeholders from both IT security and the business—and when I say business, it’s not just the C-suite, but specifically risk managers,” he said. “That’s one of the paramount things we are striving to do: get all the risk managers and CISOs better aligned and tackling situations like this.”

Snyder agreed, “There has to be appropriate alignment and I think it comes down to the risk manager and CISO having a partnership and being able to have a dialogue to ensure the organization is protected, not just from an IT standpoint, but also from an enterprise risk standpoint.”

Once developed, it is critical that stakeholders go through and practice the plan, explore the decision paths that might arise from different cybersecurity scenarios, and ensure all necessary resources are identified and contact information collected for when disaster strikes.

“A crucial mistake we see is a company buying an insurance policy or saying they have done [the right preparation], but they are not communicating the incident response plan or they are not formalizing it adequately,” Wice said. “When a bad event does happen, they are still in a spot where they aren’t making the right phone calls, getting coordinated, or making a concerted effort to communicate internally about what’s happening. That results in mistakes being made and, probably, costs incurred that don’t need to be.”

To ensure maximum coverage for those costs, the plan should also detail when to contact insurers. “Organizations must be mindful of the notice clause and cooperation clause under their policy,” Snyder explained, urging policyholders to err on the side of notifying as early as possible when contemplating any action in the event of a ransomware attack.

The planning stage is also a good time to reach out to law enforcement, namely establishing a relationship with a local FBI office. Doing so in advance, rather than searching for a contact during a crisis and going in cold, can be very helpful, Grillo said, and the FBI is often aware of emerging threats and industry-specific incidents that have not yet been made public.

It Happened. Now What?

When an attack hits, crisis responders—hopefully with incident response plan in hand—will need to call on the right resources as quickly as possible.

If the company has a cyber liability policy, the first step is contacting the insurer with notice of a potential incident, which will prompt the insurer to activate its network of third-party resources to begin or even lead incident response. It is also time to activate the organization’s established external network, should it have one.

“We first need to hire attorneys to make sure that we understand the legal obligations,” Wice said. “The attorneys will assess the associated risk, hire the forensics firm under privilege, and get them a master services agreement connected with the insured and start conducting a forensics analysis.” Forensics experts must establish how the ransomware entered the system, answering: when did the infection happen, who was affected, how many nodes were affected, and does it impact the entire network?

According to security intelligence firm LogRhythm, 72% of companies attacked could not access their data for at least two days, and 32% could not for five days or more.

“All too often, companies jump off-plan and try to go to containment immediately—they find a system has been exploited or compromised and zero in on that,” Grillo said. “The investigation step is critical to any incident response plan. You need to know what is going on and how widespread it is, then you can move to containment.” This investigation, paired with the efficacy of existing cyber hygiene practices, will determine the decision path from there. “If they’ve got your data and it’s encrypted, your options are limited. If your systems have been patched and your data is backed up, you’ve got other options to take on,” he explained.

Last summer, RIMS, the publisher of this magazine, experienced a ransomware attack. As in the majority of cases, an employee fell for a phishing email and clicked a malicious link. When the attackers struck, Mike Peters, vice president of information technology, quickly isolated the infected machine, informed key stakeholders within the organization, communicated with staff about the crisis and any appropriate action from users, and carried out the key tasks to assess, contain, mitigate and remove the threat. In short, he said, “the logical steps to take were: 1. Identify, 2. Stop and mitigate the attack, 3. Develop a plan to combat it, and 4. Recover our data.”

Peters and his team were able to get RIMS back up and running in six hours with no data loss and no ransom paid. For this successful and rather fast recovery cycle, Peters credits rigorous baseline cyber hygiene practices, including his data retention plan and approach to backups, annual disaster recovery testing, periodic spot testing, and daily monitoring for network intrusion. Paired with his own considerable training and certification as a chief information security officer, ethical hacker, and data forensics examiner, these measures negated the need to bring in forensics consultants, speeding the investigation and mitigation process.

For bigger organizations and those without such internal resources, the process can take far longer and involve a wide range of internal and external stakeholders. According to security intelligence firm LogRhythm, 72% of companies attacked could not access their data for at least two days, and 32% could not for five days or more.

When the University of Calgary suffered a ransomware attack in May 2016, investigation, response and recovery was a considerably longer process, including a week of extensive forensics and crisis management. They brought in a breach coach, retained and engaged security specialists, and assembled an emergency response team and IT incident command that worked around the clock for days on end, according to Janet Stein, the university’s director of risk management and insurance and a member of the RIMS board of directors. Communicating with thousands of users involved both high- and low-tech solutions, from the university’s emergency notification app to posters on doors around campus. Affected computers and file servers were physically unplugged or virtually sandboxed and forensics specialists traced the malware, retaining relevant forensic evidence. The team met three to four times a day, focusing on specific deliverables related to investigation, workaround solutions for users, and next steps.

Once an organization regains access to its data and systems, the response process is not quite over—refining an incident response plan is both the first and last step in any cyber crisis. “It is very easy to overlook one thing that is key in developing a truly formidable incident response plan: lessons learned,” Grillo said.

Somebody will always click the link. Or in our case, when it happened, click the link 12 times.

Such review added concrete value in the wake of the RIMS attack, Peters said. The organization assessed the existing strategy and schedule for backups, contracted with an email filtering vendor to help head off future attacks via phishing, and implemented anti-malware software. These, he said, “have made a difference by leaps and bounds.”

While Peters periodically conducts phishing tests on employees, even within a risk management association, the weakest link will always be end users, and he believes the experience has also made a significant impact on improving awareness and education internally.

“Somebody will always click the link. Or in our case, when it happened, click the link 12 times,” he said. “I don’t think we’ll ever be 100% out of the woods with our end-user community, but I think our awareness has increased tenfold.”

To Pay or Not to Pay?

It is hard to say how many ransomware victims pay the ransom. The FBI believes only a quarter of attacks are reported at all, and insurers do not necessarily hear about ransoms paid. Many victims have immature cyberrisk programs to begin with, so they are not reporting, Snyder said, and even among more prepared companies, ransoms that do not meet the deductible or concerns over the impact on premiums lead some to keep quiet.

The middle of a crisis is not the time to have that debate—those conversations need to be had in advance and a decision made about whether you will pay.

Estimates vary widely: In a study by cybersecurity firm Carbonite, 45% of businesses that had suffered an attack paid up, usually citing lack of preparation as a top determinant. Fortinet pegged the number at 42%, while 70% of respondents surveyed by IBM Security said they paid. In its 2017 Cyberthreat Defense Report, security industry research firm CyberEdge Group found that 61% of its 1,100 respondents were compromised by ransomware in 2016, of whom 33% paid the ransom and recovered their data, 54% refused to pay but successfully recovered their data anyway, and 13% refused to pay and subsequently lost their data.

“The question of whether to pay often comes up, and there are differences of opinion, not to mention the legal and law enforcement aspects of paying cyber thieves,” Grillo said. He advises that companies assess the business implications, get counsel involved, and decide on a policy before an incident ever occurs. “The middle of a crisis is not the time to have that debate—those conversations need to be had in advance and a decision made about whether you will pay.”

For Peters, it was never an option. “We never thought about paying and as long as I’m here, we will never pay,” he said. “I have the utmost confidence in our backups because we do a disaster recovery test once a year and do periodic spot tests to ensure that we can recover servers, files, computers, work stations—the necessary things to keep us running.”

According to Wice, such appropriate and adequate backups are the key factor to avoid paying. Most of Beazley’s insureds rely on their backups and as a result, he estimated the number of clients that suffered an attack and paid a ransom is “less than double-digits.”

“I wouldn’t say that we, as an insurer, should be influencing that decision, but I will say—and most of the security industry would say—as long as you have the appropriate backups in place, don’t pay,” he said. “There’s nothing you could say that would make me comfortable that, should a company pay the ransom, they are going to just get back decrypted data. You’re talking about honor among thieves here. And if you do pay, how do you know that you’re not going to be tabbed as a mark for the next exploit?”

There’s nothing you could say that would make me comfortable that, should a company pay the ransom, they are going to just get back decrypted data. You’re talking about honor among thieves here.

Indeed, the FBI, which officially discourages payment, has cited several recurring problems experienced by those who do. Paying a ransom does not guarantee an organization will regain access to its data—in fact, some never received decryption keys after paying, and there are reports of malware simply deleting the files after decryption. Upon initial payment, some enterprises were pressed for more money, while other victims who paid reported being the target of cybercriminals again soon thereafter. The FBI also points out that payments “embolden the adversary to target organizations for profit” and create a lucrative environment that may draw in more criminals.

Cyberrisk experts acknowledge, however, that from a financial standpoint, paying may be the only practical option for some enterprises.

Despite extensive incident response efforts and temporary solutions like issuing 8,000 new email addresses so users could work, the University of Calgary ultimately paid a ransom of 27 bitcoin (then about $15,000, or CAN $20,000). While Stein said the response was largely considered successful, the university endured a week of disruption and had to evaluate all the data potentially not backed up, including academic research conducted on campus. The university’s board decided that access to data and services—and mitigating the potential costs of data loss—made paying worthwhile.

“As much as you would like to take the prudent position not to pay, that may not outweigh the company’s losses, and it really becomes a business decision,” Grillo said. “Ultimately, if your data is impacted and you can’t get it back, if it’s interrupting your business or impacting your clients, there are some serious business decisions that need to be made.”

If planning to pay, the organization should involve counsel and seriously consider contacting law enforcement, Grillo advised. “You’re negotiating with criminals at this point,” he said. “When you get that far into extortion situations, it’s likely beneficial to have law enforcement involved.”

Insurance: Beyond the Bitcoin

If an organization does pay, the ransom can be covered by a cyber insurance policy. In some cases, however, since the sums requested are so low, it may not meet the deductible. “We certainly have paid cyberextortion on the cyberextortion insuring agreement, but it’s not as much as one might think,” Wice said.

Covered losses specifically from ransoms remain low at Willis Towers Watson as well. “At this early stage, it seems to be sort of a high-frequency, low-severity issue—the extortion demands are relatively low, so a lot of times, it likely falls within the retentions,” said Jason Krauss, cyber/E&O thought and product leader for FINEX North America.

Beyond the ransom funds, cyber insurance can help companies manage and recover from a variety of ransomware-related losses. Carriers and brokers have even cited such cases as the best encapsulation of the growing insurance line.

A ransomware event is really the perfect scenario to illustrate the coverages in a standalone cyber insurance policy.

“A ransomware event is really the perfect scenario to illustrate the coverages in a standalone cyber insurance policy: you have, obviously, the extortion demand, the cost to investigate the potential breach, a business interruption situation that could arise, and potential third-party claims,” Krauss said.

These cases may also be broadening the way organizations assess their own cyberrisk exposure, and impacting insurance penetration as WannaCry primarily struck regions with very low take-up rates to date. “Because of the broad nature of the attack and the fact that it spread to so many countries, WannaCry certainly got organizations’ attention,” Snyder said. “Right now, roughly 30% of organizations of all revenue sizes purchase a cyber insurance policy and 90% of those organizations are inside the United States. This attack has changed the dialogue because it’s an example for organizations that may have previously thought about cyber insurance solely as coverage for privacy risk.”

While high-profile attacks prompt companies to assess the different kinds of loss a cyber policy would cover, these ransomware cases are helping firm up answers from insurers as well. As a burgeoning line that continually evolves to catch up with the changing threat landscape, some cyber insurance provisions remain relatively untested. Particularly given the increased potential exposure for insurers, Krauss said the recent widespread attacks have prompted conversations with the market about how every insuring agreement within a cyber policy would respond and how coverage will actually hold up to claims.

Although take-up rates are rising—and the attacks and subsequent losses continue to mount—there are no signs that ransomware claims will significantly impact pricing in the near future.

“The cyber insurance marketplace is becoming much more robust, including a number of new market entrants in both the London and U.S. markets, and it’s become rather competitive,” Snyder said. “Because it’s so competitive, we haven’t seen any type of rate impact arising out of ransomware losses. Right now, we continue to see a flattening of rates and a broadening of coverage in the cyber market, and that really has not changed as a result of the increase in losses.”

Wice agreed the surge in ransomware attacks will likely not impact pricing, but he believes it may help shape the growing cyber insurance market more broadly. “Ransomware is probably going to affect capacity,” he said. “Just like with large breaches in point-of-sale for retailers, just like in the managed care space, just like in the large hospital space, once large losses hit a tower of insurance, insurers take notice. A lot of the players that recently came into the marketplace because they thought there was a growth opportunity…history would dictate that they would leave and capacity would shrink.”

Author: Hilary Tuttle

Source: http://www.rmmagazine.com